By Andreas Feix, Digital Compositor, Industrial Light & Magic

With a pandemic looming and quarantine requiring everyone to remain at home, it's not surprising that some artists have been using other creative outlets with the extra time they have.

This is also how Tucki came to be, as a free time activity, consisting of a series of clips showcasing home videos of the titular pet in everyday situations. However, the main difference is that Tucki is a dinosaur, created digitally and integrated into footage shot at home or in the neighborhood.

The ongoing project has not only helped me face some difficult times but has also served as a means to experiment with different techniques and workflows.

Creating Tucki

Amusingly, the initial inspiration for Tucki came from another quarantine pastime: watching an above-average amount of cute animal videos. Having grown up with cats, being cut off meant finding some solace in a digital equivalent.

A recurring theme of the videos was uplifting stories of rescued animals and the bonds they share with their human counterparts as a result. Not only did it provide some peculiar insight into animal behavior, but it also stuck out as a key narrative element and led to some initial ideas for fictional scenarios. Given a personal bias towards dinosaurs, it's rather obvious why the concept would pivot towards involving a prehistoric rescue animal in the end.

As it so happened, I was furloughed for a short spell during quarantine, which allowed me to develop the initial concept further and jump-start it as an actual project. I put together a 3D animatic pretty quickly, which was almost a parody of the typical animal content shared across social media. It featured everyday moments captured at home, including some of the early beginnings as a rescue dinosaur.

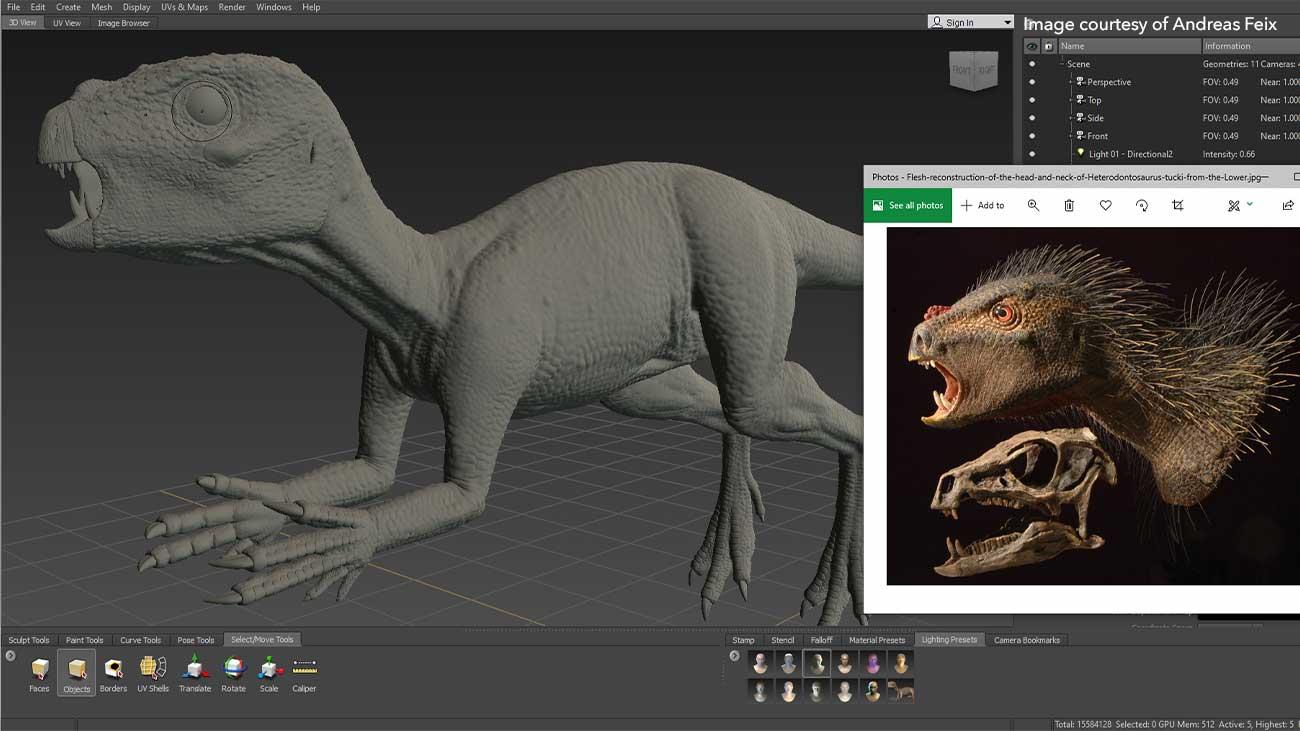

The dinosaur is based on an actual species called Heterodontosaurus tucki, which also led to its nickname. Its unusual features, including fangs and quills, added a lot of character, compared to using a more common dinosaur. The look was based on a variety of skeletal references and paleoart to ensure a realistic depiction—a 3D model of the bust, created by renowned artist Tyler Keillor, served as a major source of inspiration.

But, by the time everything was ready for a test shoot, my furlough came to an end, and my focus had to shift back to regular work. As a result, the project was quickly revamped into an open-ended series of clips. This made the whole process more flexible and took the pressure off finishing a larger project versus completing individual shots or editorials. The original animatic does still occasionally serve as the base for some of the clips being produced.

What’s more, the project was designed with little to no budget, which helped reduce the risk of sunk costs whilst also keeping the work grounded. The digital camera used was borrowed from a friend, so the biggest investment came in the form of ordering some equipment online, such as chrome balls, tripods, and checkered tape for tracking markers. Shooting on location or at home was also kept to a single person, although having to balance shooting and on-set puppeteering simultaneously did become a little tricky.

Despite appearing improvised, camera movements were often rehearsed and shot multiple times, selecting the takes most suitable for VFX work later. Chrome balls and references were shot for every new setup, and whenever possible, locations were measured to provide a reference for reconstruction, much to the confusion of socially distanced bystanders.

From the prehistoric to Nuke

Although it was initially only considered for compositing, Nuke's role gradually expanded during production.

Bringing in Nuke for prep work streamlined the whole process significantly, as plates could be imported, undistorted and matchmoved in one go, they could even be cleaned up, if not part of compositing, later. As lens settings were kept fairly consistent throughout photography, the setups for lens corrections could be easily shared and re-used across scripts, building up a small library for reference.

Matchmoving was largely done using custom tracks to ensure a more accurate solution and combined with automation for difficult situations.

Once solved, the flexibility of being able to create both proxy geometry with primitives and organic meshes based on point cloud data was incredibly valuable in rebuilding sets digitally, plus these could then be exported to 3ds Max to start animation work. Surface textures could be extracted using these geometry and projection techniques, which helped the CG lighting.

Meanwhile, the tracking data and geometry came in handy for any cleanup or prep work required, such as removing tracking markers and stand-ins for the dinosaur. The chrome ball photography was also stitched and patched up in Nuke using similar techniques, and providing panoramic environments.

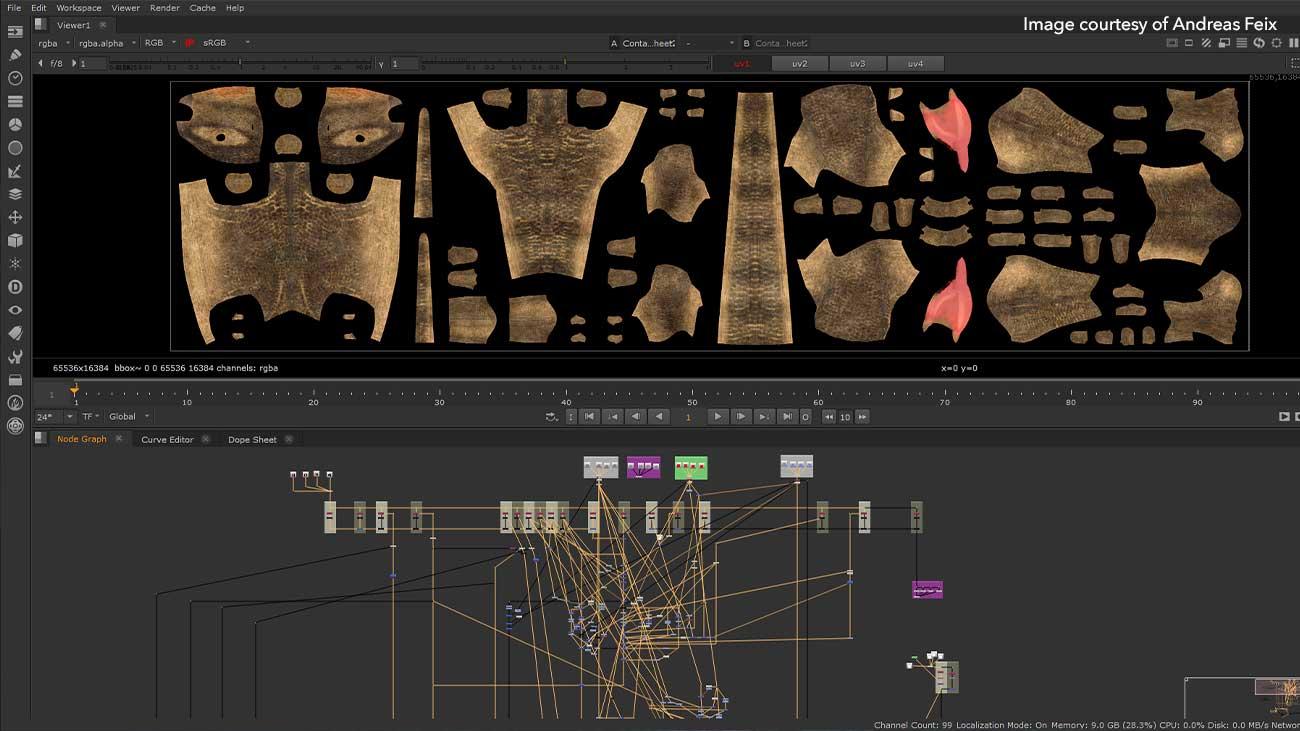

The compositing toolset also played an unusual role in the creation of the dinosaur's surface textures.

In the beginning, a variety of texture patterns and RGB mattes were painted onto the sculpt in Mudbox. This created a small library of elements which were then imported into Nuke, alongside surface maps such as normals, displacement and occlusion. The individual UV tiles were set up as different views so they could all be read and composited in parallel, similar to a stereoscopic workflow.

With all the elements prepared—even a model imported as an Alembic for additional surface data—all of the surface textures were composited together procedurally, whilst also cleaning up shader maps and providing additional treatment. This workaround had the advantage of keeping textures consistent across different elements such as teeth and claws, but also performing changes with the mindset of a compositing artist, both before and after rendering.

General modifications to the 3D render in the comp, for example using albedo or diffusing color passes, could later be copied over onto the original textures, and directly incorporated as revisions into the next iteration of renders.

A living, breathing dinosaur

The general workflow for Tucki was largely reminiscent of previous projects, particularly Citipati, by favoring a generalist approach in 3D with a larger focus on 2D and compositing work afterward.

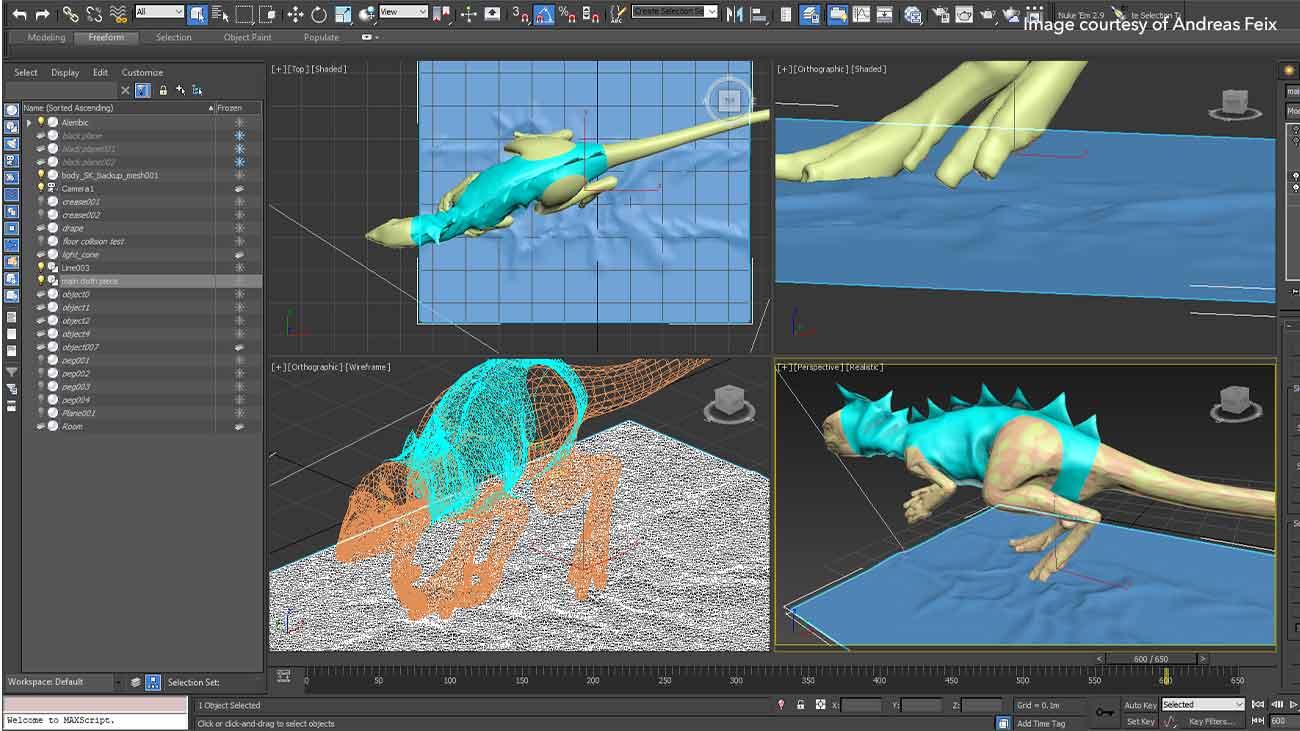

Rigging and animation were handled using 3ds Max's CAT module, with a lot of secondary details animated procedurally to suggest muscles and tissue jiggling, or tail movements being automated. To keep the spontaneity of home video, character behavior was often improvised on the fly while animating, to add in happy accidents or other small moments. Simulation work, such as cloth interaction, was mainly kept inside 3ds Max as well, although Houdini did come into play a little as well.

Lighting and rendering were done using V-Ray. To create a proper lighting set up very quickly, the chrome ball panoramas and textures from Nuke were projected onto the set geometry. This provided better lighting and material interactions while using V-Ray Lights for the main sources.

The approach to rendering setups in V-Ray was driven by the desired workflow to benefit compositing. 3D renders were divided into individual lighting and data passes and subsurface scattering was rendered as a separate element to be added in comp. Given that everything needed to be computed and managed on a personal workstation, render times had to be kept low while maintaining a certain quality level.

When it came to composite the shots, the main goal was to leverage my own professional experience to facilitate the work and streamline it, while also leaving room for experimentation. This was in part because of the workload before comp, but also to allow for re-usability and avoid potential potholes.

Starting from the first composites, many individual processes such as adding grain, artifacts, data conversions and other modifications, were turned into reusable modules and templates, which allowed for building up a brand new comp script with very little effort. One of the main tools that was put together was a group template dubbed the “Light Mixer” and based on the careful preparation of renders in V-Ray.

It took in all the individual passes of a CG element and combined them into a final image at the bottom. This allowed for full control over material and light properties with a few simple slides, including preview modes so I could individually check different properties. Allowing this flexibility in comp pretty much eliminated the need to re-render CG elements.

Some elements were even directly created in Nuke from scratch with the help of data passes. The proper reflections for the eyes were done by rendering an interactive panorama based on set geometry in Nuke, I also generated new textures such as grunge maps or dirt patterns. These could then be shared across different shots or turned into templates for reuse.

Not every bit of comp work has to revolve around a dinosaur though. Sometimes a little 2D help was needed as well, albeit for odd circumstances, such as creating a suggestive phone insert or coloring white chocolate to a more common brown tone.

The future of Tucki

Being a free-time project, there's of course some uncertainty as to how long this might continue, but it's encouraging to see the work so far as it stands on its own, and the overall positive reception is motivating as well.

There are surely more ideas ready to be produced, and with the original animatic still around as a guide, who knows, maybe in time, the initial concept will be completed as intended. As a wise man once said, life always finds a way.

Watch Tucki, the prehistoric superstar here.

Want a go at creating your own Jurassic content?

About Andreas:

Andreas Feix is a visual effects artist predominantly working in compositing as well as doing generalist work. He studied at the Film Academy Baden-Wuerttemberg from 2009-2015 and graduated with his short film Citipati which was honored with both an Annie Award and a VES Award. Since 2008, he's taken part in a variety of productions in film, television and advertising, including franchises such as Game of Thrones, Star Wars, and Jurassic World.

Currently, Andreas works at Industrial Light & Magic in London.